The article was initially published on 29th November 2023.

How can we change the climate finance system to improve accountability and ensure that decisions and policies learn from the insights of women on the front line of the climate crisis?

Women and girls are often on the front line of the climate crisis, including as environmental defenders, food producers and care givers. It has already been established that women, girls and indigenous communities are structurally vulnerable to climate change, and that the environmental crisis will worsen the gender-based inequalities that keep them impoverished and marginalised. That needs to change. But how?

RELEVANT SUSTAINABLE GOALS

To ensure that the specific needs of these groups are met, it is critical that gender-responsive climate finance reaches them where they are. Yet several critical barriers are stopping this:

- There’s no consistent reporting or single framework that allows all climate finance, including ODA, to be counted. This makes it hard to find out who is funding climate projects, let alone gender-responsive climate projects.

- The existing gender and climate markers used to tag official development assistance (ODA) are blunt instruments. They can’t adequately assess how much funding is being directed to deliver gender-responsive climate projects.

- There’s currently no way of accurately collecting data and building a data eco-system that captures both women’s experience of climate change and their contributions to climate action. This means resources aren’t well targeted.

The problems with reporting

A critical first step to improve on the transparency and visibility of climate finance is to scrutinise how climate finance is currently reported. Research from Development Initiatives (DI) and others shows a real lack of timely, accurate and consistent reporting of all climate finance flows. This prevents us from understanding who is giving what climate finance to whom, and how much is being given.

Currently gender or climate finance provided as ODA is measured by ‘marking’ the finance with either the Development Assistance Committee’s gender marker, or its climate marker, or both. Yet neither marker is a reliable way to accurately assess if funding is being directed to deliver gender-responsive climate projects.

This is compounded by the fact that (as it’s a donor-reported field) donors can choose how they interpret the guidance for applying the markers. While general uptake of the markers has been improving, several donors continue to lag in applying the marker to some or all their flows, especially those beyond ODA.

What’s more, some donors take a very liberal approach to applying the markers – particularly in marking projects as ‘significant’ – reducing the value of analyses that aggregate without interrogating other project information (which often reveals that the project is only tangentially related to gender equality or climate).

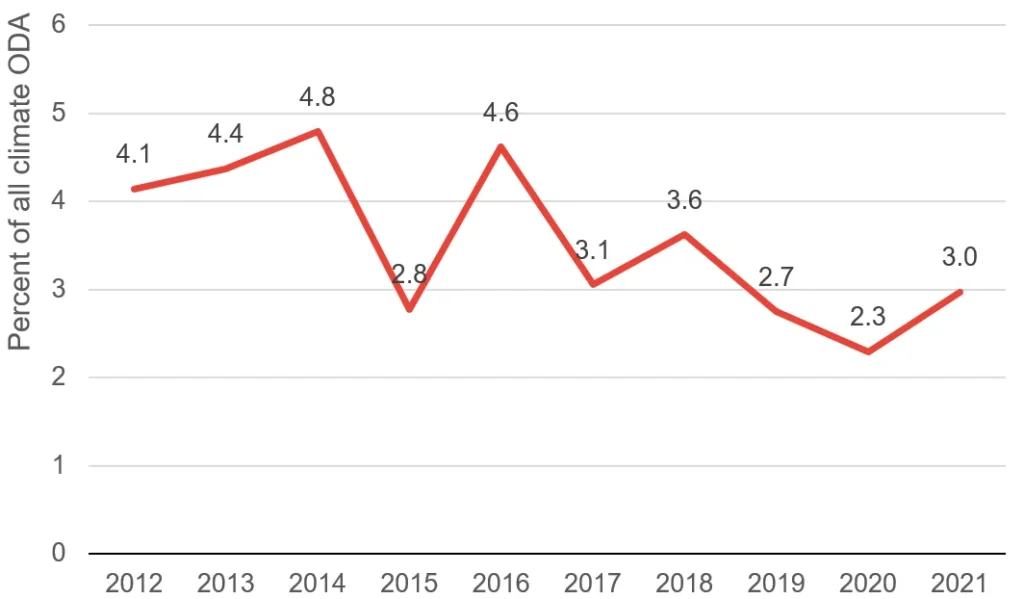

Lastly, trend analyses are difficult – if not meaningless – due to the changing quality of reporting by donors, which means that increases in funding under the marker can’t be understood as increasing funding to gender-equality-focused climate projects. However, what’s worse is that, even using this approach, in 2021 only 3.0% of climate ODA incorporated gender equality as a principal objective (according to OECD data).

Percent of climate ODA with a principal gender focus (2012-2021)

It’s hard to measure how effective climate finance data is at addressing the needs and lived experience of the women on the front line of climate change. The gender marker doesn’t capture this; it’s driven by donor self-assessment, which isn’t developed with the inclusion of women’s voices and is far removed from an understanding of the intersectional needs of the most marginalised.

Understanding women’s experience of climate change

About 80% of the world’s food is produced by smallholder farmers. Women make up on average 43% of this agricultural labour in the Global South. The climate crisis is making their lives much harder: changes in temperature and rainfall mean longer days (on top of the unpaid labour that they already contributing, including care of children and the elderly); climate-resistant seeds are an additional cost; there can be a struggle to feed their families. Unless we can find a way of capturing this intersecting experience in official data systems, the lived experience of women and girls will continue to be invisible in our current data ecosystem. Including them is critical to ensure targeted policies and resources.

As outlined by the IPCC – and reiterated in the valuable expert paper on gender-responsive climate finance, presented by Eurodad to the Expert Group Meeting of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW68) – “an intersectional approach contributes to better capture the diversity of adaptive strategies that men and women adopt vis-à-vis climate change”. There must be a way of capturing the intersecting experiences of women, girls and other marginalised groups in official data systems to better target policies and resources. Filling this data gap needs to happen alongside ensuring that investments into our foundational data ecosystems for gender and climate are coherent, sustainable, nationally owned and values based.

DI is a champion of both the inclusive data charter and the data values project, and we have seen first-hand the value that the inclusion of voices can have across the development data value chain – from conceptual development to collection, and from analysis to use – as well as the value of novel sources of data directly provided by citizens and communities in the form of citizen-generated data.

As outlined by UN Women, the impact of the climate crisis is not seen just in environmental factors and economic variables, but has a huge impact on health, education and wider developmental factors, especially for women and girls. For example, there are greater rates of child marriage in areas that frequently experience droughts; and in drought-affected areas there are higher adolescent birth rates; and increases in the incidence of violence against women. That is why it’s vital that any investments into gender and environmental data takes an ecosystem-level approach.

What DI is doing

At DI, we have been researching how investments into data ecosystems translate on the ground, with a particular emphasis on foundational data systems that ensure everyone counts and is counted. We have found that (often well-intentioned) investments are implemented in a way that can create:

- duplication across the ecosystem (both in terms of surveys and administrative data systems);

- competition between line ministries, preventing data sharing and efforts towards harmonisation;

- and (in areas experiencing conflict and sustained crisis) parallel systems that aren’t nationally owned.

Ultimately, this undermines the domestic resource mobilisation needed to ensure that these data systems are sustainable, comprehensive and nationally owned.

These lessons must be learnt to ensure that investments in gender and climate ecosystems don’t make the same mistakes or suffer the same consequences.

To improve this, institutions, donors and governments must focus on:

- A more coherent and shared understanding of climate financing and how it should be categorised.

- Inclusion of and leadership from women in the conceptual definitions to ensure that gender-responsive climate finance meets the needs of those at the forefront of tackling the climate crisis.

- Accountability mechanisms (based on these inclusive definitions) to ensure consistent and transparent reporting of both commitments and disbursements.

Lead image courtesy of UNWomen / Michael Goima

Authors : Mariam Ibrahim , Fionna Smyth , Claudia Wells , Euan Ritchie