Multi-year droughts (MYDs) have become drier, hotter, and more frequent, spreading across the planet at an alarming rate.

For fourteen consecutive years, northern Chile has battled extreme drought. The American Southwest endured eight years of unrelenting dryness. In southern Australia, three years of parched land devastated agriculture and water supplies. These are not isolated weather events but part of a global trend of worsening, prolonged droughts, a crisis that has intensified over the last 40 years.

RELEVANT SUSTAINABLE GOALS

New research, published in the journal Science and led by the Swiss Federal Research Institute (WSL), paints a stark picture: multi-year droughts (MYDs) have become drier, hotter, and more frequent, spreading across the planet at an alarming rate. The affected land area has increased by nearly 50,000 square kilometers per year—more than the size of Switzerland—since 1980.

As temperatures rise and rainfall patterns grow erratic, these mega-droughts are reshaping ecosystems, crippling agriculture, and threatening water security for millions. And for Asia and the developing world, where climate resilience remains fragile, the implications are particularly dire.

How Climate Change Fuels Drought Intensification

Droughts have long been part of the Earth’s natural climate cycle, but what makes this era different is the intensity, frequency, and duration of these events. The study attributes the acceleration of MYDs to three key factors:

- Rising Temperatures: Higher global temperatures increase evaporation from soil and vegetation, intensifying drought conditions.

- Reduced Rainfall: The precipitation deficit—how much rain is “missing” compared to historical averages—has increased by 7mm per year for the world’s worst MYDs.

- Vicious Feedback Loops: As droughts deplete vegetation, less moisture is released into the air, leading to fewer clouds and even hotter, drier conditions.

Dr. Dirk Karger, the study’s lead author, explains: “Everybody was talking about droughts becoming more frequent with climate change, but there was no clear database to confirm it. We now have a baseline to measure the true impact of MYDs.”

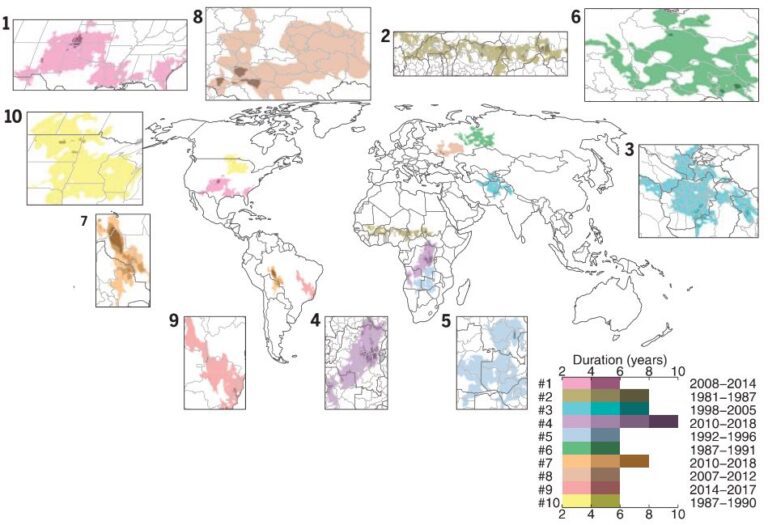

Mapping the World’s Worst Droughts

The study identified more than 13,000 MYD events between 1980 and 2018, spanning every continent except Antarctica. Some of the most devastating included:

- Eastern Congo Basin (2010–2018): The longest recorded MYD, affecting 1.5 million square kilometers of tropical forest.

- Mongolia (2000–2011): The worst ecological damage, reducing vegetation by nearly 30% and devastating livestock-dependent communities.

- Chile (2010–2019): A “mega-drought” that depleted reservoirs, slashed agricultural output, and extended the wildfire season.

Not all landscapes respond to drought in the same way.

- Grasslands suffer the most significant vegetation loss, visible via satellite imagery as green areas turn brown.

- Tropical and boreal forests can withstand short-term dry periods, but when prolonged drought strikes, tree mortality soars, and ecosystems collapse.

- Tundra regions remain relatively unaffected, as their growth cycles are dictated more by temperature than rainfall.

With MYDs expected to grow longer and more intense, these findings raise a critical question: How will ecosystems adapt—or fail to?

The Human Cost: Agriculture, Water Scarcity, and Migration

The impact of MYDs extends far beyond environmental devastation. These prolonged dry spells cripple agriculture, disrupt hydropower generation, and lead to mass displacement.

- Food Security at Risk: Failed crops mean food shortages and price hikes, disproportionately affecting lower-income nations. In Asia, where rice is a staple crop, irregular monsoons threaten production.

- Water Crises: Rivers, lakes, and reservoirs dry up, triggering severe water rationing. Cities from Chennai to Cape Town have already faced “Day Zero” water crises.

- Climate Migration: Drought-induced poverty drives mass migration, exacerbating regional instability. Sudan, Myanmar, and Afghanistan have all seen drought-driven displacement in recent years.

Dr. Maral Habibi, a climate researcher, warns: “Rising temperatures amplify drought through increased evaporation and worsening precipitation deficits. Without action, this trend will only accelerate.”

Asia and the Developing World: The Most Vulnerable

For Asia and the Global South, where agriculture-based economies and dense populations leave little room for climate resilience, the stakes are even higher.

- South and Southeast Asia rely on the monsoon cycle, but shifting rainfall patterns are creating years of either extreme flooding or prolonged drought.

- China and India, two of the world’s biggest food producers, face severe groundwater depletion from overuse and climate-induced scarcity.

- The Middle East and Central Asia, already grappling with desertification, are seeing aquifers run dry, leading to political tensions over water access.

The study urges governments, international organizations, and researchers to develop better drought prediction tools and regional adaptation strategies to prevent humanitarian crises.

While the science behind MYDs is clear, the global response remains inadequate.

Experts call for AI-driven drought forecasting, improved water management, and investment in resilient agriculture, including:

- Drought-resistant crops that require less water to thrive.

- Cross-border water-sharing agreements to prevent resource conflicts.

- Climate funding for the Global South, helping developing nations mitigate the worst effects of MYDs.

Dr. Ruth Cerezo-Mota of the National Autonomous University of Mexico stresses: “We need more data, better climate models, and increased investment in adaptation. The world must prepare for these extreme events before they become unmanageable.”

The world is entering a new era of climate extremes, and multi-year droughts will be one of its most devastating features. The data is clear: MYDs are longer, drier, and hotter than ever before—and they will only worsen unless urgent climate action is taken.

For policymakers, scientists, and citizens alike, the question is no longer if these droughts will define our future—it’s how we choose to respond to them today.