Millions of people migrate each year to work in India’s sugar fields under extreme heat, harsh conditions and debt bondage

This story is the second of Climate Home News’ four-part series “The human cost of sugar”, supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Karan Gautam Wavhale, 20, wanted to join the Indian Army, but it was not to be. Instead, he became a labourer, travelling over 200km from his home in Koyal, in Maharashtra’s Beed district, to toil in the sugar fields of Karnataka.

He is one of millions who migrate with the sugar season each year. Heatwaves, drought and floods brought by climate change make the working conditions increasingly harsh. And when yields are low, many workers get trapped with debts they cannot repay.

“It is about survival,” Wavhale told Climate Home News. “Due to water shortages several months each year, there is just no work for us here… there is no option for us but to migrate.

“It is not just the story of our village. There are dozens of villages like ours.”

Climate Home News visited Koyal, about 450km from India’s financial capital Mumbai, in August. The villagers were preparing for the upcoming sugarcane harvest season in October. Here, climate change is worsening the already harsh conditions for workers.

Most of the village’s 2,500 people travel to neighbouring states Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh or western Maharashtra for seasonal work in sugarcane fields. There are no other jobs for them in Koyal and many residents hold government-issued Below Poverty Line (BPL) cards.

India is the world’s largest producer and consumer of sugar and the second-largest exporter. 50 million farmers are involved in India’s sugar industry, cultivating sugarcane in an area spanning almost five million hectares (50,000 sq km).

According to the Indian government, during last year’s sugar season more than 500 million metric tonnes of sugarcane were produced in the country. It is a record that the government is celebrating, but it comes at a high cost to vulnerable migrant labourers.

Almost half a million labourers migrate from Maharashtra’s Beed district each year to work in the sugarcane fields

Scorching heat

More and more, these migrants have to work in scorching heat – temperatures exceeded 46C in Maharashtra in April. This takes a severe toll on their physical and mental health, leading to extreme fatigue, anaemia and joint problems as well as depression and anxiety, according to a report by Oxfam India.

Workers prepare the fields, sow seeds, irrigate the crops, cut them with sickles and load the cane onto tractors for transport to the sugar mills in the region. The days last between 13 and 16 hours, over a 4-5 month season.

Sampat Lakshman, a 49-year-old migrant labourer, told Climate Home News that he and his colleagues work day and night during the sugarcane harvest season.

“If we cut the sugarcane during the day, we have to stay till late at night to load it in [the] trucks. There’s no timetable of any sort… there’s no time to get tired,” said Lakshman.

Sampat Lakshman, a sugarcane labourer from Beed district in Maharashtra, lives in a tiny hut with his wife and five children

Debilitating accidents

Labourers are frequently injured by a misplaced machete, heavy load or vehicle accident. Snake bites are common. In extreme cases, some suffer permanent disability, amputation or even death.

Wavhale’s younger brother Sachin was killed in a devastating vehicle collision in 2021.

“We were returning home in a vehicle which ferries workers. The driver tried to avoid an accident. [Because of this] several people fell off the vehicle… when the driver reversed the car, the vehicle crushed my brother’s head,” Wavhale told Climate Home. Sachin’s name was scribbled on the wall of his small, poorly lit home in Koyal.

“Several people suffered injuries in the accident, three people including my brother died on the spot,” he said. “One died a few months later due to injuries.”

Raghu Govind Patwade of Beed district suffered spinal injuries in 2016 when a tyre of a tractor trolley drove over him while he was resting in a sugarcane field in Karnataka. Although he survived, it has not been possible for him to work since then.

“I suffered multiple fractures including one on my hip. Since then, I have been bedridden. I can’t work now and I am stuck at home. I have a bag attached to pass urine,” he told Climate Home News.

“There are deep-rooted concerns in the way the [sugar industry] functions, regarding human rights violations, migrant labour and the living conditions [of labourers], child labour and child marriages, and women’s rights,” said Pooja Adhikari, Business Global Coordinator, Global Value Chains at Oxfam Germany, who has carried out extensive research into the industry.

Minimal facilities

The labourers in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh told Climate Home that when they work in the fields there are hardly any facilities for them, whether it is food, water, toilets, healthcare or electricity.

The sugar mill provides some materials for makeshift shelters from rainfall, extreme heat or cold, Lakshman said. Their earnings are “not enough to fill the stomach but only to ensure that we don’t starve”.

According to the report by Oxfam India, “the tents are small and inadequate to give complete shelter” and “do not have water, electricity supply or toilets.”

A sugarcane labourer plants sugarcane cuttings in Satara district of Maharashtra.

Missed schooling

In Maharashtra around 1.5 million people migrate each year with their children, according to Oxfam. Of those, nearly 500,000 migrate from Beed district, the hiring hub for cane cutters.

Migrant labourers are integral to sugarcane harvesting, Mantare Hanuman, a social activist in Maharashtra, told Climate Home News. “It is labour-intensive work… it requires labour at every step, whether it is sowing or harvesting,” he said. Machines are expensive and rarely used.

During the dry season in Beed district, from November to May, villages face severe seasonal unemployment. Wavhale, who left school when he was 15, said nobody wants to stay behind and work in the fields in Koyal, because they are paid close to nothing – a mere $1-2 per day.

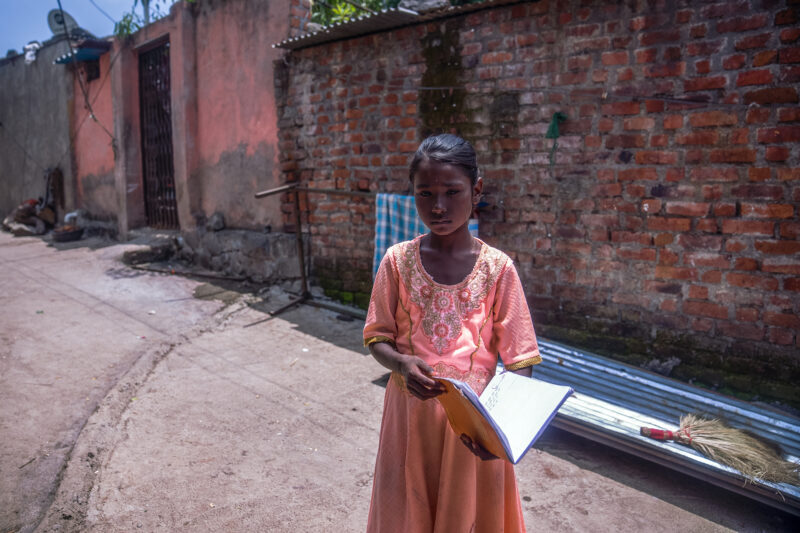

Once the labourers migrate, their villages are left deserted. About 200,000 children younger than 14 accompany their parents during the cutting season and live with them in temporary huts, missing school.

“I know that their education suffers but I have no option but to take them with us,” said Lata Chandrasen Patole, a resident of Paargaon in Beed district. “There is no one else to take care of [them], [provide them with] food and [look out for their] safety.”

Hanuman said parents fear their daughters will face physical and sexual abuse if they are left behind. Many children drop out of school altogether at a young age and join their parents in the fields, he said.

The children of

Read More