After Armenians fled the conflict-torn region, the COP29 host nation has launched a huge reconstruction effort to polish its green credentials

Neat rows of new houses with solar panels on their turquoise roofs radiate out from the quiet central square of Aghali, a government-branded “smart village” in south-western Azerbaijan. A path lined with yellow bushes leads to the river, where a state-of-the-art hydropower plant produces clean electricity for residents.

Aghali is a pioneering example of Azerbaijan’s plan for “green” reconstruction of the territories it captured after a long, bloody conflict with Armenia, centred on the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh mountainous enclave.

Hundreds of Azeris displaced from the region in the early 1990s have moved back to Aghali, a local government official told Climate Home.

“The emotional link to these territories is very strong even though 30 years have passed,” the official said. “Our people are happy to be back”.

The government says more than 100,000 Azeris will return to populate the 30 or so new towns and villages planned across the area by 2026, which are expected to run mainly on clean energy and aim for “net zero” emissions.

Yet a more troubled story lies beneath the shiny surface presented by the authorities – part of Azerbaijan’s efforts to polish its green credentials before the COP29 UN climate summit it will host in November.

Some 136,000 ethnic Armenians who had called Nagorno-Karabakh their homeland fled in a mass exodus during a two-part military offensive by Azerbaijan that started in 2020 and ended last autumn.

For Armenian authorities and some human rights and legal experts, the drive amounted to “ethnic cleansing” – a phrase used in a European Parliament resolution on the conflict. A spokesperson for COP29 told Climate Home the Azerbaijan authorities “categorically reject this view”.

With the fighting now over, the two sides are engaged in talks to build a lasting peace. They struck an initial agreement to establish border demarcations in April, but hopes of a swift breakthrough on a permanent solution remain slim.

Meanwhile, displaced Armenians have said publicly they fear the heritage sites and homes they hastily left behind will be erased under a giant construction effort. Evidence of this was seen last month by Climate Home on a press trip organised and sponsored by the COP29 Presidency team, which controlled access to locations and sources in the region.

‘Net zero’ vision

Azerbaijan has built its prowess, both on and off the battlefield, on the strength of its vast oil and gas reserves. Around 60 percent of the government’s budget is financed through the sale of fossil fuels, primarily via export to Europe.

Last month, Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev called oil and gas “a gift from God” at the Petersberg Climate Dialogue in Berlin, signalling continued investment in increased gas production. That is despite signing up, like all countries, to a global agreement to transition away from fossil fuels “in keeping with the science” at the COP28 UN climate summit in Dubai last December.

Nonetheless, as its capital Baku gears up to host COP29, Azerbaijan also wants to show off its efforts to adopt clean energy and cut planet-heating emissions to the outside world.

Nagorno-Karabakh, and the surrounding provinces, lie at the centre of this push. The government has declared a “green energy zone” here, adding a dozen hydropower plants, and seeking to attract foreign investment in solar and wind.

Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev in front of a screw turbine hydro power plant in Zangilan, one of the territories recaptured in 2020. Photo: Azerbaijan Presidency

Across the country, the government wants renewables to make up 30 percent of its installed electricity capacity by 2030 – up from 7 percent in 2023. The main motivation is to reduce the use of gas in its own power stations so that more of it can be shipped to Europe, President Aliyev said during an event at ADA University in Baku in April.

Azerbaijan is also planning to achieve “net zero” carbon emissions in Karabakh by 2050, as outlined in its latest national climate action plan (NDC) submitted under the UN climate process. It says that “to revitalise the territories liberated from occupation”, the government will establish “smart” settlements, promote “green” energy zones, agriculture and transport, and reforest “thousands of hectares”.

For Anna Ohanyan, a senior scholar in the Russia and Eurasia programme at the US-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “it’s greenwashing of an ethnic cleansing, pure and simple”.

“Azerbaijan is putting a stamp on the territory as a way to legitimise the conquest of Nagorno-Karabakh and doing so under the pretence of helping fight climate change,” she told Climate Home.

The COP29 spokesperson said in emailed comments that this view “has no basis in fact”, adding that Azerbaijan is rebuilding houses for its citizens who were internally displaced during the conflict, “according to UN sustainability standards”.

Disputed territory

Territorial disputes over the Nagorno-Karabakh region have a long and complex history.

“Azerbaijan and Armenia – both are convinced this is historic patrimony of their people,” said Audrey Altstadt, a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who specialises in Azerbaijan.

As the Soviet Union set about governing its far-flung provinces in the 1920s, then Commissar of Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, ruled that the region should be part of Soviet Azerbaijan, even though ethnic Armenians made up 94% of its population at the time.

In the 1980s, alongside the fall of the Soviet Union, tensions began to rise after Nagorno-Karabakh’s governing authorities declared their intention to join Armenia and Azerbaijan reacted by attempting to suppress separatists.

After the two sides gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, clashes between them escalated into an all-out war.

By the time fighting stopped three years later, Azerbaijan had suffered a crushing defeat, losing not just Nagorno-Karabakh but also a sizable chunk of territory around it. Ethnic Armenians declared a separatist republic in the region with the backing of Armenia.

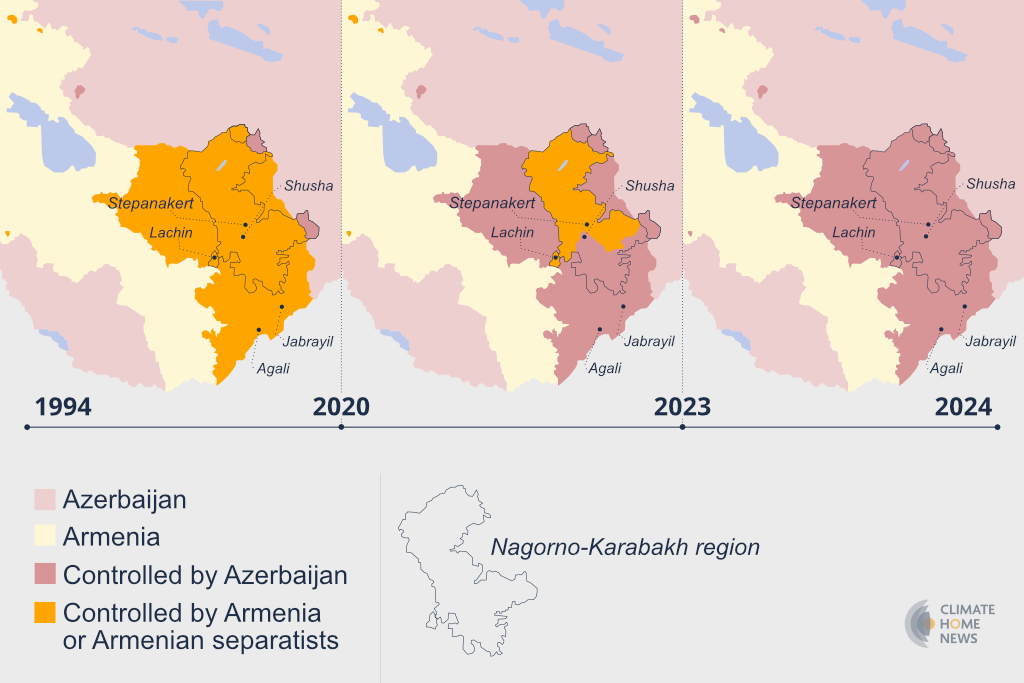

Evolution of territorial control over Nagorno-Karabakh, and surrounding districts, from the aftermath of the 1994 war until today. Graphic: Fanis Kollias

Some 870,000 Azeris abandoned their homes in the captured area and Armenia itself, while around 300,000 ethnic Armenians fled Azerbaijan, according to the United Nations’ refugee agency.

For 15 years the conflict remained frozen, while international actors – led by the United States, France and Russia – tried, and failed, to find a peaceful resolution.

Azerbaijan’s autocratic president, Aliyev, took matters into his own hands in September 2020, mounting a large-scale military offensive on Nagorno-Karabakh. Powered by more sophisticated weaponry, and backed by Türkiye, Azeri forces prevailed during a 44-day war that claimed the lives of at least 7,000 people – including over 100 civilians.

Under a ceasefire agreement signed in November 2020, Azerbaijan gained a significant proportion of Nagorno-Karabakh, including the coveted town of Shushi – called Shusha by Azeris – as well as winning control of adjacent districts.

Soon afterwards, Baku announced a colossal programme to rebuild and repopulate the region, establishing “green energy zones” in Nagorno-Karabakh and East Zangezur.

Rebuilding ‘from scratch’

Deep behind a string of police checkpoints, the plan is proceeding apace. It includes Aghali, one of the “smart” villages created by the government to accommodate Azeri citizens displaced from the area three decades ago.

“Everything we build here, starting from houses to schools, is based on the element of solar,” said Vahid Hajiyev, special representative of the Azerbaijan presidency in Jabrayil, Gubadli and Zangilan districts, addressing a group of international reporters.

“The whole area had been devastated,” added Hajiyev, saying it was largely abandoned and littered with mines after Armenia captured it. “We’re doing everything from scratch and that gives an opportunity to do it right.”

A view of Aghali, a “smart” village created by the Azerbaijani government in the territories retaken from Armenia, in April 2024. Photo: Matteo Civillini

A nearby screw hydro turbine provides electricity for the whole village, while homes are equipped with solar water heating systems, officials told Climate Home.

“Smart agriculture” projects are being developed to give work to the more than 860 people who, according to government figures, have already moved into the village, with hundreds more expected to join them soon, they added.

Climate Home was not able to talk to any of the residents, besides government officials, and was not shown around the homes.

Aghali offers a template for around 30 similar villages the Azeri government plans to erect across the captured regions. They are just one part of the mammoth construction drive in the Karabakh area, bankrolled by Baku to the tune of just under $2.5 billion a year – around 12% of total public spending.

While the official vision projects an eco-paradise, in Baku’s breakneck drive to put it into practice, the landscape currently resembles a sprawling construction site, as seen by Climate Home and shown by satellite images.

Travelling up the windy road to Shusha-Shushi just before midnight, the headlights of dump trucks and cement mixers pierced the near-total darkness.

They are the backbone of a giant effort to lay down thousands of kilometres of roads and railways and throw up brand-new airports, vast conference halls, hotels and apartments.

Globally, construction is among the most polluting industries, contributing around 10% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2022, according to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

In March 2022, the Azerbaijan government invited observers from UNEP to assess the environmental situation in the territories it had gained, after accusing Armenians of large-scale destruction and contamination of the water and soil.

The UNEP team documented “chemical pollution of water” and “deforestation” as a result of activities in dozens of mines and quarries carried out by the Armenian administration “with inadequate environmental oversight and supervision”.

But it also found that Azerbaijan’s building drive, then still in its infancy, was already putting further strains on the environment, as well as causing climate-heating emissions, thereby “adversely impacting the zero-emission goal for the region”.

The construction of new roads was “having a significant impact on forest cover”, its report stated, while the infrastructure programme “placed a significant burden on finite natural raw materials” extracted from local quarries to make cement or asphalt.

The construction drive is altering the landscape in Nagorno-Karabakh. Photo: Matteo Civillini/April 2024

The COP29 spokesperson said Azerbaijan is following the recommendations of the UNEP report and that “a number of mitigation measures have been undertaken” to curb the environmental footprint of the works.

“We believe that the net impact of the reconstruction effort will actually contribute to Azerbaijan’s climate change and decarbonisation goal,” the spokesperson added.

Nagorno-Karabakh’s net zero target has yet to be extended to the rest of the country. Currently Azerbaijan has a goal to reduce emissions 40% by 2050 and has promised to submit a new NDC that is aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5C, which is due by early 2025.

Environmental blockade

In December 2022, environmental concerns became a weapon in the long-running dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijani eco-activists blocked the Lachin Corridor, the only road connecting the region to the outside world and a vital supply line for food and medicines.

They were ostensibly demonstrating over the impact of mining in the breakaway region. But, according to close watchers of the conflict, the protesters had been sent there by Baku – a claim denied by the COP29 spokesperson.

At the time, one protester told Climate Home that representatives from the Ministry of the Environment were also present. On many other occasions, the Azerbaijan government has cracked down on political dissent, according to human rights groups.

When, four months later, Azerbaijan erected a permanent checkpoint on the road to “prevent the illegal transportation of manpower and weapons”, the sit-in ended. But the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh continued with only limited amounts of aid trickling in.

Shortages of food, medications and fuel plunged the region into a humanitarian crisis, according to UN human rights experts.

“In the end, it was hard to even find bread. There were women and kids queuing all night for a piece of bread,” recalled Siranush Sargsyan, an Armenian journalist from Nagorno-Karabakh, in an interview with Climate Home. “Even if they didn’t kill all of us, they were basically starving people.”

On September 19 2023, Azeri forces launched a lightning attack on the parts of Nagorno-Karabakh still controlled by ethnic Armenians in what Baku called “an anti-terrorist operation”. Within 24 hours, the de-facto government of the enclave surrendered and announced the republic would cease to exist the following January.

Fearing violence and persecution, over 100,000 ethnic Armenians – nearly the entire remaining population – fled their homes in Nagorno-Karabakh and sought refuge in Armenia.

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh region arrive at the Armenian border in a truck in September 2023. REUTERS/Irakli Gedenidze

“[The] liberation of territories was a main goal of my political life. And I’m proud that these goals have been achieved,” President Aliyev, whose family has ruled over Azerbaijan for the past 31 years, said last December. “I think we brought peace. We brought peace by war.”

Now in full control of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan is doubling down on its efforts to reshape the region and move tens of thousands of Azeris there. “We will continue the ‘Great Return’ campaign until all those who were forced from their homes can go home,” the COP29 spokesperson said, referring to internally displaced Azeris.

Government officials told Climate Home that ethnic Armenians are also welcome to go back, but only if they stick to the conditions imposed by Baku.

Journalist Sargsyan said returning to Nagorno-Karabakh under Azeri control is out of the question as she fears for her safety. “I left everything there”, she said. “But I would rather die than end up in a prison in Azerbaijan.”

Heritage destruction

Meanwhile, ethnic Armenians fear the huge Azeri construction drive now underway will erase most, if not all, of their legacy.

Nijat Karimov, a special adviser to Azerbaijan’s presidency, told Climate Home that Baku had destroyed Armenian government buildings in Nagorno-Karabakh for “safety” reasons, without giving specifics. He added that Azerbaijan’s government had since “repaired and rehabilitated” the villages.

A day later, Climate Home travelled past what little remains of Karintak village (known as Dashalti in Azeri). Nestled in a gorge sitting just below Shusha-Shushi, it was home to a few hundred ethnic Armenians until Azeri forces took over at the end of 2020.

Now nearly the entire settlement appears to have been razed to the ground, as Climate Home witnessed. Mounds of disturbed soil surround a large mosque, under construction, and a church, one of the few original buildings left standing.

Read More