Governments could not agree to keep talking formally about limiting plastic production up until the final round of treaty talks in November

Hopes for a new global treaty to include limits on rocketing production of plastic worldwide have faded after government negotiators sidestepped the issue at UN talks in the Canadian capital of Ottawa earlier this week.

At the fourth – and penultimate – round of talks, negotiators did not agree to continue formal discussions on how to cut plastic production before a final session in the Korean city of Busan set for November, making it less likely that curbs will be included in the pact.

Peru’s negotiator said his country was “disappointed”, while the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law said governments had sacrificed “ambition for compromise”.

“The pathway to reaching a successful outcome in Busan looks increasingly perilous,” said Christina Dixon, ocean campaign leader at the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Big Oil’s plan B

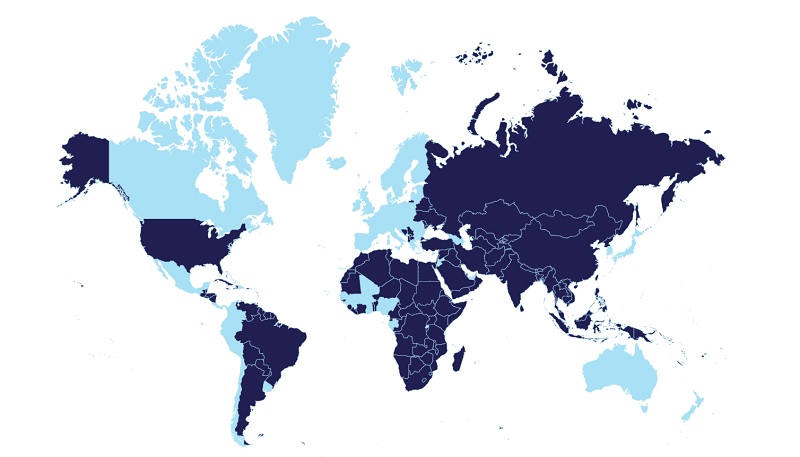

While some governments led by a self-described “High-Ambition Coalition” have pushed for measures to reduce plastic production – which is expected to nearly double in G20 countries by mid-century – major oil and gas-producing states like the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran have favoured an emphasis on recycling over producing less.

The members of the self-described “High-Ambition Coalition” are in light blue (Photo credit: CREDIT)

Plastics are made from oil and gas, and their production accounts for 3% of greenhouse gas emissions. Fossil fuel companies are betting that as demand for oil and gas for energy use falls, they can compensate by selling more of their products to plastic manufacturers.

The Ottawa talks were marred by complaints from scientists and campaigners that plastics industry delegates were harassing and intimidating them, while secretively-funded, pro-plastics adverts were placed around the venue by a right-wing Canadian lobby group.

‘Unsustainable’ plastic use

The governments of Rwanda and Peru have been leading the push for a strong global deal to rein in plastic pollution, winning international approval for the talks to craft a treaty at the United Nations Environment Assembly in 2022.

In Ottawa last month, they asked governments to give their backing to formal negotiations on how to reduce the production and use of plastics, with support from the 65 member states of the High-Ambition Coalition.

While recognising that “this is an issue characterised by divergent views”, Rwanda’s negotiator told delegates “there is at least a convergence on the desire to develop an instrument that is fit for purpose guided by science – and to do so, the question we must ask is what are sustainable levels of production and consumption?”

“Science tells us that current and projected levels of plastic consumption and production are unsustainable and far exceed our waste management and recycling capacities. Moreover, these levels of production are also inconsistent with the goal of ending plastic pollution and limiting global warming to 1.5C,” she added.

‘More than a number’: Global plastic talks need community experts

But governments including Russia, Saudi Arabia and India are opposed to focusing on production curbs. The Ecuadorian chair of the talks, Ambassador Luis Vayas Valdivieso, did not include production in the list of topics to be officially discussed further before the final negotiations in South Korea.

Instead, he proposed expert groups on how to fund efforts to tackle plastic pollution and on criteria for identifying types of plastic product “of concern”. Governments accepted this, finishing their discussions at 3am on Tuesday.

Compromise welcomed

Peru expressed disappointment at the decision not to focus on production – but Russia’s negotiator welcomed it, saying that issues like the design of plastics and recycling are the “cornerstone of the future agreement” and so the talks should focus on them.

India’s delegate said the negotiations should be conducted in “a realistic manner and with consensus”, adding that “plastics have played an important role in development of our societies”.

Saudi Arabia’s negotiator praised the talks’ chair for “looking into those topics that bring convergence”, while many countries including China, the US and the European Union said the Ottawa outcome was a good compromise.

Southern Africa drought flags dilemma for loss and damage fund

Late on the last night of the talks, the EU had proposed holding another full session of negotiations before Busan, but that was blocked by Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

David Azoulay, an observer for the Center for International Environmental Law, accused developed countries that style themselves as leaders on plastics of giving up the fight “as soon as the biggest polluters look sideways at them”.

In response to the lack of progress on production curbs, a group of countries led by the Pacific island nation of Micronesia put out a statement promising to continue talking informally about the issue and to keep it on the agenda. Thirty-two countries signed the “Bridge to Busan” initiative, including Nigeria, France and Australia, and more are expected to join later.

Micronesian negotiator Dennis Clare told Climate Home that its signatories “recognise that we cannot achieve our climate goals, or our goal of ending plastic pollution, without limiting plastic production to sustainable levels”.

Delays, intimidation and harassment

The four rounds of talks held since 2022 have been marked by delays, which some observers say are deliberate tactics by countries like Saudi Arabia and Russia.

At the second session in Paris last May, negotiators spent two days discussing voting rules, an issue which many thought had already been resolved.

And the third round in Nairobi in November failed to agree on intersessional work leading to Ottawa, after opposition from Russia and Saudi Arabia.

In Ottawa, the meeting was marred by complaints of intimidation and harassment from campaigners and scientists against some of the 196 lobbyists from the plastic and fossil fuel industry present in the halls.

Tensions rise over who will contribute to new climate finance goal

Bethanie Carney Almroth, a ecotoxicology professor at the University of Gothenburg who co-chairs the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective P

Read More