With tropical forests across Asia vanishing across under pressure from plantations, mining, and infrastructure, a bold new financial mechanism is emerging out of Brazil; the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF).

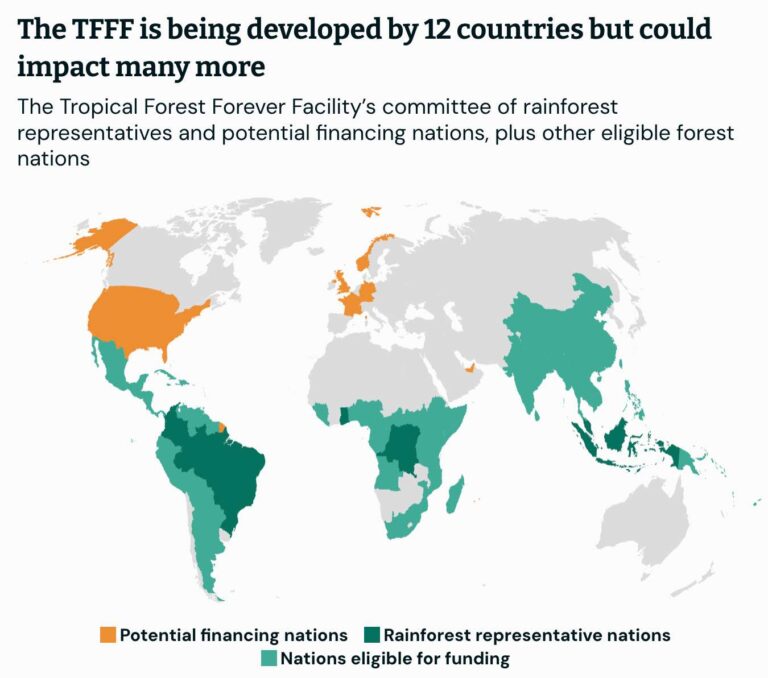

SINGAPORE – Slated for official launch at the COP30 climate summit in Belém last November, the TFFF aims to raise a staggering US$125 billion for tropical forest conservation across 76 countries. Its model promises shift in forest finance, offering annual payments to countries that not only halt deforestation but proactively persevere standing rainforests.

The implications for Southeast Asia – home to some of the world’s most carbon-dense and biodiverse rainforests – could be transformational. Yet experts warn that how this fund is governed, invested, and distributed will determine whether it becomes a game-changer or another cautionary tale.

RELEVANT SUSTAINABLE GOALS

FROM DEFORESTTATION PENALTIES TO PRESERVATION INCENTIVES

Unlike earlier mechanisms like REDD+, which rewarded emissions reduction from avoided deforestation, TFFF proposes direct payments for standing forests. Tropical nations with deforestation rates below 0.5% of their total forest area and a declining trend can receive up to US$4 per hectare annually.

But there’s a catch. For every hectare deforested, countries face steep deductions ranging from US$400 to US$800. Degraded forests, which appear intact on satellite images but have suffered ecological damage, incur US$100 per hectare in penalties.

“The great innovation is to create an incentive that includes a disincentive in the mechanism itself,” said Tasso Azevedo, a leading Brazilian climate expert and co-architect of the idea.

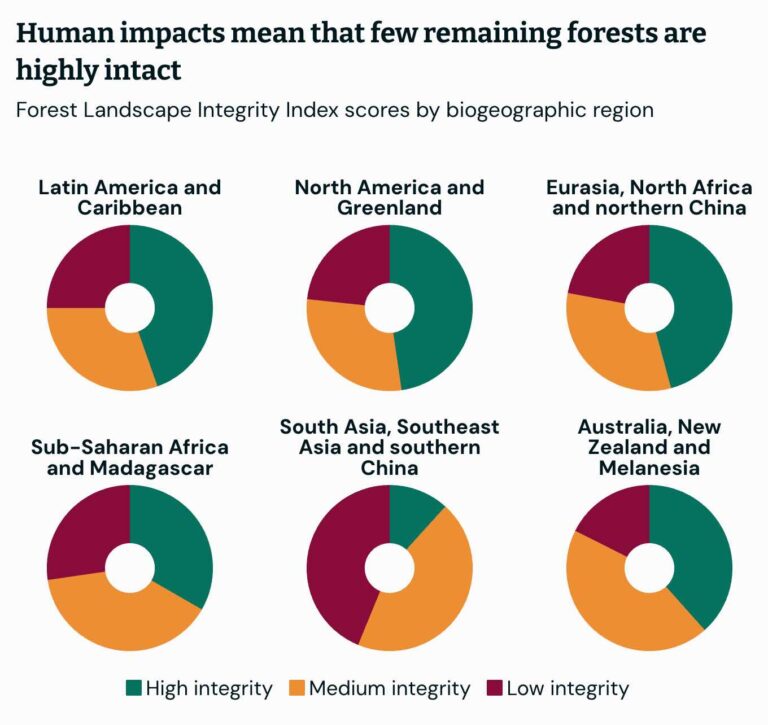

This shift is particularly relevant for Southeast Asia, where countries like Indonesia and Malaysia have made strides in reducing deforestation but still battle forest degradation from fires, fragmentation, and unsustainable land use.

DESIGNED IN BRAZIL, BUILT IN THE TROPICS

Unlike Conceived by the Brazilian government with support from conservation groups like the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and IPAM, the fund has drawn interest from 12 nations. Its backers include both tropical forest custodians and wealthy donor countries like Norway, Germany, the US and the UK.

To sidestep REDD+’s carbon quantification complexities, TFFF will use satellite monitoring to track forest cover. Countries must submit annual reports and invest at least 20% of the payments into Indigenous and local community programs.

In Southeast Asia, where traditional communities are often stewards of intact ecosystems, this requirement could catalyze long-overdue financial recognition of Indigenous land rights and conservation roles.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CONTRADICTION IN CLIMATE FINANCE

If successful, the TFFF could deliver US$4 billion annually from interest alone on its investments. Its structure blends public pledges with capital market fundraising – sovereign wealth funds and pension funds are seen as key investors, attracted by long-term, low-risk returns.

But some, like Azevedo, question the logic of relying on high-yield bonds from the very countries the fund aims to support. “Rich countries would reap the financial benefits while tropical nations bear the financing burden,” he cautioned.

Furthermore, is US$4 per hectare a strong enough incentive to compete with profits from palm oil, mining, or logging? Critics argue the real power of the mechanism lies not in its per-hectare payments, but in its deterrence through penalties.

SOUTHEAST ASIA : THE LITMUS TEST FOR TFFF’S PROMISE

For nations like Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, the TFFF could unlock significant funding to scale up existing conservation success and shift towards zero-deforestation development.

But implementation will require more than funds. Countries must enhance forest monitoring systems, develop inclusive national plans, and align policies with Indigenous rights and climate goals. Indonesia’s experience with the moratorium on primary forest clearance, or Malaysia’s state-level conservation initiatives, offer models for scaling.

Given the region’s exposure to climate risk, from typhoons to forest fires, and the economic value tied to natural capital, the stakes are immense.

As COP30 approaches, pressure is building for the TFFF to deliver not just dollars, but justice. Governance, transparency, and equitable access for local communities will define whether this fund becomes a milestone or mirage in global forest finance.

Carlos Rittl of WCS, one of the fund’s architects, put it plainly: “If the TFFF is able to mobilise investments on the scale we want, of 125 billion dollars, it will truly be the largest source of resources for forest protection we have ever seen in history.”

In Southeast Asia, where the future of rainforests often lies in tension between development and preservation, the future depends not just on money — but on trust, accountability, and political will.

You may also be interested in :

Southeast Asia’s Alarming Primary Tropical Forests Loss: Indonesia, Laos, and Malaysia Among Top 10