For much of the past two decades, the loudest voices in the debate over carbon capture and storage (CCS) were often the critics: The equipment was too expensive or too prone to breaking down. Perhaps most damning was the accusation that the technology would extend the life of fossil fuels and delay cleaner, longer-term solutions.

Now the dynamics have shifted. CCS projects are growing at record rates. The technology continues to improve, economic incentives have aligned and the growth of AI and data centers has increased demand. The critics have not been mollified, but the momentum is with the industry — suggesting that any company with hard-to-abate emissions in its supply chain should engage with the arguments.

“It’s been like a snowball rolling down a hill in terms of corporate interest and investment in the sector,” said Jessie Stolark, executive director of the Carbon Capture Coalition, an industry group.

Global growth

CCS offers a seemingly simple decarbonization solution: Rather than replace coal power stations, steel plants and other facilities that rely on fossil fuels, why not capture and store the carbon dioxide that the infrastructure emits? In many cases, this involves pushing the gas over an absorbent material, compressing the captured CO2 and piping it to a geological reservoir for permanent storage.

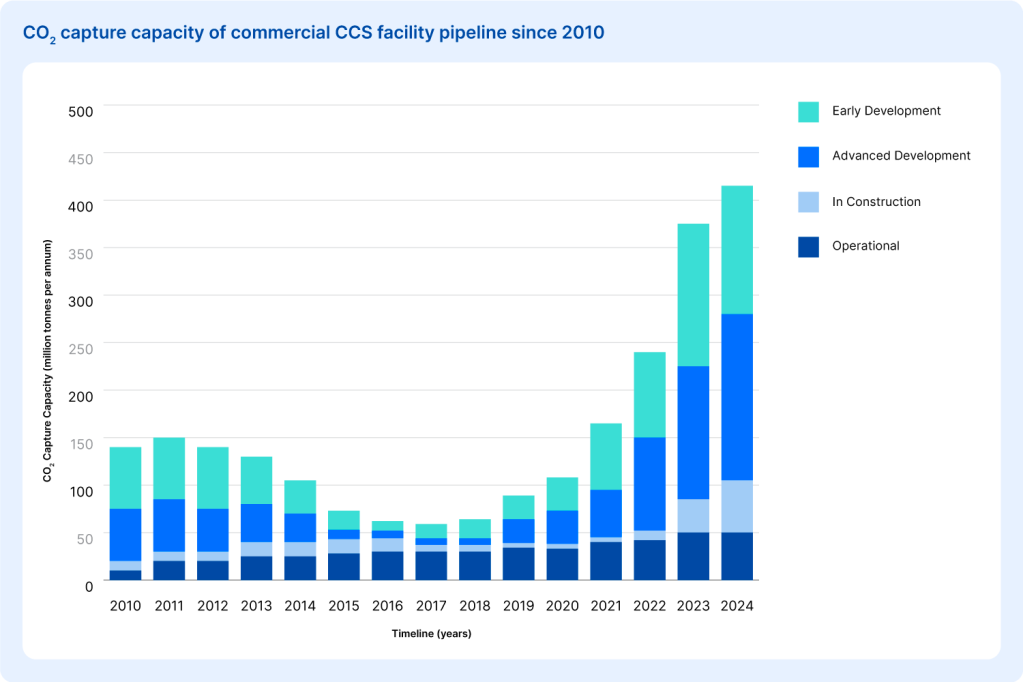

The idea is simple, but during the first half of the 2010s high costs and technological setbacks led to a decline in the capacity of projects in development. Then the tide turned. A federal CCS tax credit, known as 45Q, was made more valuable in 2018 and more valuable still, as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, in 2022. The number of projects operational or in development globally grew from 392 to 628 between 2023 and 2024, according to the Carbon Capture Coalition. The U.S. is the leader, with more projects than the next four countries — the U.K., Canada, Norway and China — combined.

The Louisiana Clean Energy Complex, a hydrogen production facility under construction in Ascension Parish, illustrates the trend. Air Products, the industrial giant behind the project, says that 95 percent of the 5 million tons of CO2 emitted annually by the facility will be captured and stored, which the company claims makes it the world’s largest capture and permanent sequestration project.

Air Products did not return a request for more information, but an analysis published this month by the capture coalition puts capture and storage costs at between $100 and $200 per ton of CO2. The exact price depends on the maturity of the technology used and the concentration of the gas in the waste stream, with higher concentration streams — which includes hydrogen facilities — tending to have lower costs.

More million-ton projects

Other huge projects are coming soon. In early April, a consortium of companies announced plans for an ammonia plant, also in Ascension Parish, that will capture and store more than 2 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. (The parish is part of “Cancer Alley,” a heavily industrialized area with elevated rates of the disease.) Two weeks later, ExxonMobil revealed plans to capture 2 million tons of CO2 from a natural gas power plant near Houston, Texas.

The bullishness of CCS investors is also evident at the 140,000 square-foot factory opened in Burnaby, British Columbia earlier this month by Svante, a manufacturer of filters that capture carbon dioxide from industrial emissions.

The factory can produce enough filters to capture 10 million tons of CO2 annually and its opening follows a $145 million investment round for the company. A confluence of factors is driving the industry forward, said Claude Letourneau, Svante’s CEO, including tax credits and the green premium that some manufacturers can charge for low-carbon commodities, such as hydrogen.

Smaller companies with innovative solutions are waiting in the wings, hoping to ride the industry’s momentum. Carbon Clean, a London-based startup, has designed a capture unit that fits into a shipping container, which it says is half the size of conventional systems.

“The biggest challenge for implementing carbon capture is the real estate,” said Aniruddha Sharma, Carbon Clean’s CEO “Nobody has any space.” Following a successful test at a fertilizer plant in Abu Dhabi, the company is now working on further tests in Saudi Arabia and Canada.

Companies that have emissions from hard-to-abate sources — fertilizer, steel, cement — in their S

Read More