The latest text suggests a rich government-led finance goal of $250 billion a year by 2035, which the African Group called “totally unacceptable”

This article will be updated throughout the day and an edited version will be sent out each evening as a newsletter – you can sign up here.

In today’s bulletin:

-

- Draft text proposes $250bn per year in public climate finance by 2035

- Rich nations react

- Developing nations split over slices of finance pie

- Fossil fuel transition removed from drafts on cutting emissions

- Campaigners: No deal better than a bad deal

- Saudis oppose anti-fossil fuel and pro-human rights language

Draft text proposes $250bn per year in public climate finance by 2035

On Friday, a keenly awaited, slimmer version of the draft text for the post-2025 climate finance goal (NCQG) finally proposed some figures for the amounts that should go to help developing countries tackle climate change.

The text offers a core goal of $250 billion a year by 2035, which would come from a wide range of sources “with developed country parties taking the lead”. This is far below what developing country groups have been asking for in the three years of talks.

Ali Mohamed, Kenya’s special envoy for climate change and chair of the African Group of Negotiators, called the proposed figure “totally unacceptable”, adding, “$250 billion will lead to unacceptable loss of life in Africa and around the world, and imperils the future of our world”. But a US official said it would be a tough target to meet.

“It is [a] joke,” said African Group finance negotiator Alpha Kaloga in a post on X. “BAD DEAL,” he added. His words come hours after campaigners held a press conference to say no deal on finance was better than a bad deal.

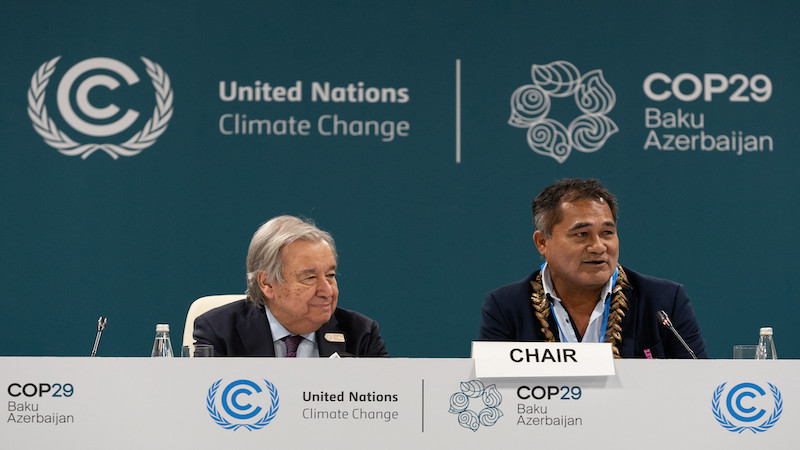

Samoa’s Minister Toeolesulusulu Cedric Schuster, chair of the AOSIS group, and UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. (Photo: UN Climate Change – Kiara Worth)

The Alliance Of Small Island States (AOSIS) said in a statement that the text shows “contempt for our vulnerable people” and called it a “shoddy placebo goal”. “We appeal to the moral conscience of those who proclaim to be our partners to stand with us,” they added.

Bolivian negotiator Diego Pacheco, who represents several large emerging economies, told Climate Home the goal was “not serious” and not aligned with the Paris Agreement.

The new public finance target – which would replace the existing $100-billion-a-year goal – would contribute to a wider goal of at least $1.3 trillion a year by 2035 “from all public and private sources”, the text says.

Climate finance is not a hand-out.

It’s an investment against the devastation that unchecked climate chaos will inflict on us all.

It’s a downpayment on a safer, more prosperous future for every nation on Earth.#COP29

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) November 22, 2024

Developing countries had called for an overall goal of around that size, but wanted $600 billion of it to be public money with the rest consisting of private investments mobilised by government cash. They also wanted a larger share to be provided as grants.

Leading economists Amar Bhattacharya, Vera Songwe and Nicholas Stern, who are co-chairs of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, said the $1.3 trillion is in line with their analysis of needs for developing countries excluding China. But they said the $250-billion core figure “is too low and not consistent with delivery of the Paris Agreement”.

The NCQG should commit developed countries to provide “at least $300 billion per year by 2030, and $390 billion per year by 2035”, they added, calling those higher targets “feasible”.

Reaching those amounts would require stepped-up direct bilateral finance from developed countries, much higher ambition on the part of the multilateral development banks, and improved private finance mobilisation, the economists noted in a statement.

On Friday evening, Brazil’s environment minister Marina Silva backed the economists’ figures, which she said should serve as the “start of a journey”. The annual sum of $250 billion in the current text would not amount to additional money on top of current levels of climate finance if inflation were taken into account, she told journalists.

Veteran climate activist Harjeet Singh called Friday’s proposal “a disgrace” and called on developing countries to reject it. “To add insult to injury, this paltry sum includes loans and lacks the crucial commitment to grant-based finance, which is essential for developing nations to both address climate impacts and transition away from fossil fuels,” he said in a statement.

Yalchin Rafiyev, Azerbaijan’s COP29 lead negotiator, told journalists that the $250 billion in the current text “doesn’t correspond to our fair and ambitious goal”, adding that consultations with governments would continue. “We hope that during this COP we will make progress.” A new version of the text was expected on Saturday morning.

Joe Thwaites, senior advocate for international climate finance with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said his team’s analysis showed it would be “very possible to get to a higher number” than $250 billion per year in public provision. That could be achieved solely through reforms already promised by multilateral development banks and modest increases in government-to-government finance “below historic growth rates”.

On the thorny question of who should pay towards the new goal, the draft text says developed countries would take the lead and “invites” developing countries “to make additional contributions” which would be “to or supplementing” the core goal.

It “affirms” that any contributions would not affect whether a country is “developed” or “developing”, or whether it can receive climate finance.

Rich nations react

Reacting to the text, a senior U.S. official said “it has been a significant lift over the past decade” to meet the current $100-billion-a-year goal.

The official added that “$250 billion will require even more ambition and extraordinary reach. This goal will need to be supported by ambitious bilateral action, [multilateral development bank] contributions, and efforts to better mobilise private finance, among other critical factors.”

German delegation sources said the country’s team would reach out to “important negotiators” such as Kenya (chair of the African Group), Brazil, Samoa (chair of the Alliance of Small Island States) and UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

“Now is the time to build bridges to move the negotiations forward,” they said in a statement. “It will certainly be important to stay in touch with China, industrialised countries and the presidency tonight.”

Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan said: “This is not at a landing ground yet, but at least we’re not up in the air without a map. Lots of work still needs to be done. We‘re working with allies from all around the world, especially the most vulnerable, to ensure an ambitious and fair outcome.”

A UK government source said “the current text doesn’t make the headway we are looking for but gives us a platform to negotiate from”. They added: “There is a hard but achievable path ahead in the final hours.”

Germany’s Jennifer Morgan speaking with fellow negotiators on Thursday morning. Photo: UN Climate Change – Kiara Worth

Developing nations split over slices of finance pie

The previous finance text had options for minimum amounts of the core goal that would go to sub-groups of developing countries, namely the world’s poorest countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS). But the latest version has none.

This is an issue that has divided developing countries, with LDCS and SIDS advocating for minimum floors for themselves.

New UN carbon market standards are a step change in protecting people and planet

In Thursday’s plenary, developing countries that are not LDCS and SIDS – like Pakistan and Saudi Arabia – spoke against them. Pakistan, which has suffered catastrophic floods in recent years, said it was “unfair to restrict access to countries that are facing the brunt of climate catastrophes”.

After Friday’s text was released, AOSIS said the floors must be added back for the COP to be a success. They added: “It is regrettable that the groups that oppose the floor are the very groups that currently receive a concentration of climate finance provided and mobilised.”

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres working behind the scenes on COP29’s official final day. Photo: UNFCCC / Kiara Worth

While an earlier draft text said 20% of the finance under the goal should be provided through the UNFCCC’s multilateral climate funds – like the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Global Environment Facility, the Adaptation Fund and the loss and damage fund – the new version weakens that to just a “significant amount”. Currently, less than 5% of funds go through these entities.

Developing countries prefer to receive funding through these entities as the conditions are usually better than those offered by multilateral development banks and rich governments’ aid agencies. They also have a degree of control over how the GCF runs, with half the seats on its board.

Fossil fuel transition removed from drafts on cutting emissions

Among the wave of new texts released this Friday, the COP29 presidency unveiled two mitigation drafts that removed all mentions of last year’s landmark decision to “transition away from fossil fuels”, after Saudi Arabia blocked oil and gas references.

Countries discussed how to cut carbon emissions under two strands of the talks: a non-binding process called the Mitigation Work Programme and a review of climate policies called the Global Stocktake, which was last year’s main COP outcome.

In the Global Stocktake, the presidency’s proposal removes all mentions of fossil fuels that were still in a previous version of the text. Instead, it only includes a reference to “paragraph 28” of last year’s decision, where the fossil fuel transition was included. But the draft still leaves an option open to remove even this language.

Saudi Arabia opposed any mention of fossil fuels, refusing to single-out any sectors (see more below).

The Global Stocktake draft also leaves out mentions to the global goal agreed at COP28 in Dubai to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030. Instead, it focuses on expanding global energy storage capacity to 1,500 GW by 2030 and “adding or refurbishing” 25 million km of power grids by 2030 and an additional 65 million km by 2040. Both of these are new goals not featured in last year’s decision.

It also leaves out a pledge from last year’s outcome to reverse deforestation by 2030.

Adaptation Fund head laments “puzzling” lack of pledges at COP29

The text will serve to inform next year’s round of climate plans, which originally had the deadline of February 2025 to submit nationally determined contributions (NDCs). After several countries announced at COP29 they would miss that deadline, the new Global Stocktake draft mentions a deadline of November 2025 for new NDCs.

Meanwhile, the Mitigation Work Programme draft keeps a weakened shape that was revealed yesterday, when the COP presidency cut the text from 10 to 3 pages. Several countries complained about the state of this decision at yesterday’s plenary session, with Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan calling it a “big step back”.

The NCQG climate finance goal was also stripped of its emission-cutting provisions, as it previously included a mandate that countries could only count as climate finance the funds that contribute to the energy transition. This was removed from the current draft.

The package of mitigation decisions “leaves any progress on mitigation ambition” as merely “options”, said Alexandra Scott, senior associate of climate diplomacy at Italian think-tank ECCO. “That is risking a collapse of these talks.”

Shady Khalil, global policy senior strategist at Oil Change International said that “while insufficient”, the Global Stocktake’s reference of the fossil fuel paragraph from last year’s decision was a “crucial political signal that needs to be protected.”

“Restating previous agreements is not going to solve the climate crisis. We need concrete action by countries,” Khalil said in a statement.

At an earlier plenary on Wednesday, Bolivian negotiator Diego Pacheco said, speaking on behalf of several large developing countries, that developed countries were asking emerging economies to cut carbon emissions without providing the necessary finance.

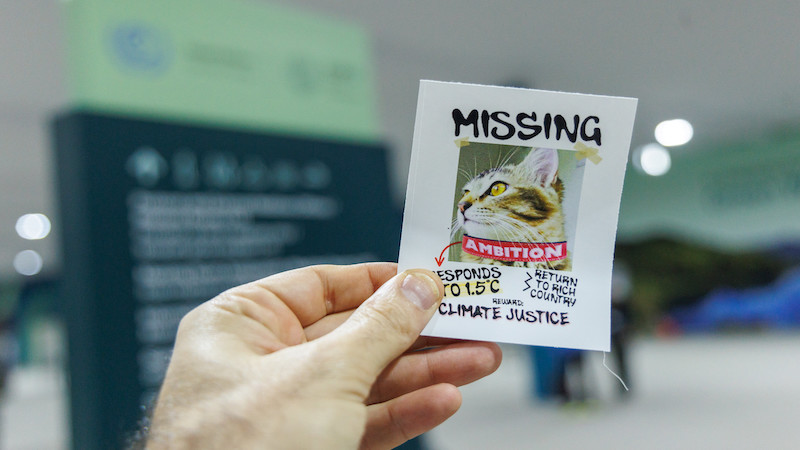

Campaigners: No deal better than a bad deal

Campaigners during the ‘No Deal is Better than a Bad Deal’ press conference. Photo: UN Climate Change – Kiara Worth

Speaking before the new draft texts were released, climate justice campaigners called on governments to walk away from the summit rather than accept a weak outcome on behalf of workers, women and vulnerable communities around the world.

They insisted that no deal in Azerbaijan would be preferable to a “bad deal”.

Mohamed Adow, founder of Kenya-based think-tank Power Shift Africa said securing a strong deal for $1.3 trillion in international public finance as developing countries are demanding is central to success. “There can’t be a COP outcome if the rich world don’t step up and put forward an ambitious climate finance goal that meets the needs of the developing countries – period,” he said.

Developed and developing nations remain far apart on the amount of the new goal, as well as who should contribute towards it, as pressure grows on wealthier emerging economies – including China and the Gulf nations – to pay up too. Those countries don’t want to be put on a par with industrialised countries that are historically more responsibl

Read More