Emerging economies reject an informal number being floated for government provision under the new goal and say they won’t join the donor pool

This article will be updated throughout the day and an edited version will be sent out each evening as a newsletter – you can sign up here.

In today’s bulletin:

- Large developing countries reject “$200 billion” climate finance figure

- Developing states: COP29 mitigation focus “totally imbalanced”

- Adaptation talks gridlocked over finance

- “Divide in the room” on technicalities of carbon markets

- Australia and New Zealand pledge loss and damage cash

Large developing countries reject “$200 billion” climate finance figure

An amount of around $200-300 billion being discussed privately as the international government finance provision towards the new climate finance goal (NCQG) – the main outcome expected at COP29 – has been strongly rejected by large developing countries.

Speaking at a stocktaking plenary this Wednesday, Bolivian negotiator Diego Pacheco said on behalf of the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) group – which includes big emerging economies like China and India – that the figure was unacceptable.

“We are unable to fathom this $200 billion to step up ambition in developing countries,” said Pacheco. “This is unfathomable. We cannot accept this.”

When asked his opinion on the $200bn figure at a press conference later in the evening, Pacheco responded by just saying: “Is it a joke?”

With three days to go until COP29 officially ends, developed countries have yet to reveal publicly the amount of public international finance they will put on the negotiating table for the NCQG.

This week Politico reported that the EU was internally discussing a figure of $200bn-300bn a year by 2035 as the overall donor part of the goal – but it has refused to be drawn on this publicly.

On Wednesday afternoon, Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan told reporters that the EU is taking the question of numbers and assessing possible sources of finance “extremely seriously”.

“We want [the goal] to be feasible, but ambitious. And one reason why there’s no German or no EU number yet – well, we don’t just want to pluck a number from the sky,” she said. “We are working towards a modern and fair new approach to climate finance,” she added.

She noted that the numbers for the size of the goal, as well as the structure and the thorny issue of whether to expand the contributors beyond the traditional pool of rich nations “will be part of the end-game package” at COP29.

As climate-vulnerable countries, we know what kind of finance we need

Time constraints are now raising nerves at the conference halls. Speaking on behalf of the G77 group of all developing countries, Ugandan negotiator Adonia Ayebare said, “We need a figure as a headline of the text. The rest will follow. I used to be a member of the press, the headline is important – sometimes more than the context.”

The chair of the African group of nations, Ali Mohamed, said that, while they had hoped to have made some progress by now, there has only been “radio silence” from developed countries. “This is very frustrating and disappointing,” he told journalists at COP29.

At the plenary, the Bolivian negotiator also reiterated a refusal by the LMDC group to open up the base of climate finance contributors – which developed countries have pushed for – to include China and wealthy Gulf states. “This is a super red line,” emphasised Pacheco.

Coalition against fossil fuel subsidies expands but misses initial targets

Chris Bowen, Australia’s environment minister who is jointly tasked with facilitating discussions on the NCQG, reported back to the plenary that the figures being discussed for government provision to an overall “mobilised” goal of $1.3 trillion included $440 billion, $600 billion and $900 billion – all amounts that have been proposed by developing countries.

Co-chair Yasmine Fouad, Egypt’s environment minister, said discussions on the “structure” of the climate finance goal are “still hearing diverging views”. These refer to the different types of finance that can be counted towards the goal – controversially, including private investments.

Negotiators reconvened for further consultations during the day, with the aim of producing new texts on finance and other key issues overnight.

Stephen Cornelius, WWF’s deputy global climate and energy lead, said that with the COP29 “end game” fast approaching, “we are still missing urgency from the negotiations”.

“All the difficult issues – how much climate finance, who pays it and who can receive it, as well as mitigation and adaptation – remain unresolved. These issues need political guidance as well as more technical work,” he added.

He urged the COP29 presidency to exercise “authority and diplomacy” to find an ambitious common ground by Friday, when the summit is due to close.

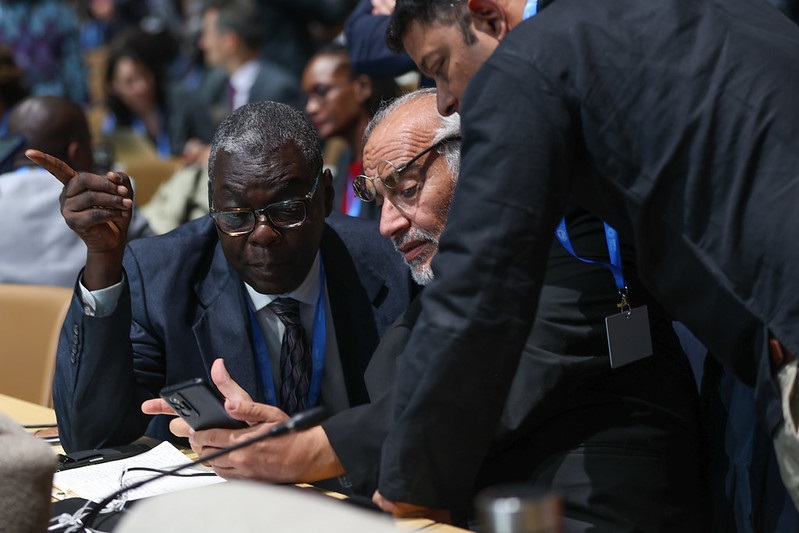

Cuban negotiator Pedro Luis Pedroso (left) and Bolivian negotiator Diego Pacheco (centre) in discussions at the COP29 opening plenary last week (Picture: Kiara Worth/UNFCCC)

Developing states: COP29 mitigation focus “totally imbalanced”

A new row over old disagreements on how to cut carbon emissions emerged on Wednesday at COP29, with large developing countries expressing “concern” in the plenary over “totally imbalanced” talks on climate mitigation.

Reading a statement from the Like-Minded Developing Countries, Bolivia’s Diego Pacheco called on the Azeri presidency to “restore balance” to the negotiations, which the group views as being dominated by “the interests of some”.

“All we hear is mitigation, mitigation and more mitigation. In fact, the mitigation and the [Global Stocktake] items are being treated with a lot of care. The process is totally imbalanced at the moment,” said Pacheco, referring to the lack of progress on finance and adaptation.

In Baku, talks on cutting emissions have faced serious divisions. The COP presidency had to intervene after Saudi Arabia threatened to get them postponed until mid next year, in what some observers called “non-constructive” blocking of the negotiations.

Countries have still to agree on which section of the talks is the best place to discuss emissions-cuts and transitioning away from fossil fuels at COP29. It could sit either in an ongoing but non-binding process called the Mitigation Work Programme or with the “UAE Dialogue” stemming from the Global Stocktake – the main outcome from last year’s COP.

India, donor countries give up on Just Energy Transition Partnership – German official

The European Union has been pushing for a strong outcome on mitigation at COP29, with its climate action commissioner, Wopke Hoekstra, saying on Wednesday that countries should not go back on what they have signed up to at previous climate summits.

“The last COP was very specific about transitioning away from fossil fuels – and that implementation thereafter should be embarked on,” he told journalists in Baku. “At the very least, we should take that as a floor – but frankly speaking, we as the European Union expect that we move upwards, given that there is so much to be done in this realm.”

In Baku, the decisions on mitigation could expand on how to implement key agreements made at COP28, including provisions to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030 and triple renewable energy capacity by the same year – as well as the landmark decision to “transition away from fossil fuels” in energy systems.

The Bolivian negotiator also criticised developed countries’ progress on cutting emissions, saying “it is all just talk”. He called on developed countries to go carbon neutral by 2030, while lamenting that mitigation discussions have been about reducing developing countries’ reliance on fossil fuels.

At G20, Brazil’s president Lula da Silva opened the second day of the summit by sending a similar message, as he called on developed countries to bring forward their 2050 goals for net-zero emissions to 2040. “Even if we are not walking [at] the same speed, we can all take one more step,” he said in his speech.

A group of demonstrators at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, demand negotiators to speed up the transition away from fossil fuels. (Photo: UNFCCC/Flickr)

Adaptation talks gridlocked over finance

Negotiations on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) were also stuck over developed countries’ unwillingness to provide finance as well as a lack of clarity on indicators for measuring progress, ministers and observers said on Wednesday.

The environment ministers of Costa Rica and Ireland told the stocktaking plenary that countries were divided on how to close the huge gap between adaptation funding and needs.

The GGA – which is enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement – aims to build the resilience of vulnerable countries to the impacts of climate change. To do that, developing countries need an estimated $215 billion-$387 billion a year, according to the 2024 UN Adaptation Gap Report.

Disappointed by the deadlock in the talks, the African Group’s chair Ali Mohamed said “adaptation is Africa’s lifeline”, calling on developed countries to “triple – don’t double – adaptation funding by 2025”. Rich countries made a promise back in 2021 to double their adaptation finance by next year to at least $40 billion, for which they say they are on track.

Mohamed said there is a need to “shift from loans to grants” for adaptation – which generally doesn’t generate returns – adding that every day of delay makes the challenge more expensive and difficult.

Diego Pacheco, Bolivia’s lead negotiator, said it was “quite unfortunate” that text on providing financial and technical aid for developing countries to adapt was being argued over.

Only 58 countries so far have put together national adaptation plans (NAPs), he noted, adding that without finance provision, the GGA would not be achieved.

Richard Klein, senior research fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute, said he suspected that talks on the GGA would end in a “disappointing” conclusion at COP29 – one where “progress is acknowledged, but more work is needed”.

“Divide in the room” o

Read More